Dating is not perennial. It has its roots in the late 19th century. Urban workers, often living in small apartments with extended family, could not engage in the ritualized calling practices of the more respectable classes or the wholesome, old-fashioned courtship found in rural communities.

If you can’t call on a girl at her house because she lives in a cramped tenement with her parents, five siblings and demented grandmother from the Old Country, you might instead spend a hard-earned nickel and take her out to see a show or maybe visit a dancehall. Thus, dating was born.

It was déclassé at first, something only low-class girls did. In some cases, the line between dating and sex work could be blurry. But by the 1910s, dating had become trendy among upper-class young people, particularly college students. It was a bit edgy—a way to get to know someone without being under the thumb of your parents. Within a decade, it had spread to the middle classes, eventually becoming the norm for all but the most traditional.

Dating has a lot of downsides. For a full century, young men have complained about the cost of dating and often feel they are not getting their money’s worth. The sexual revolution did not ameliorate these issues. Perhaps they made them worse. Many young women feel degraded by the pressure to “give” physical affection or even sex “in exchange” for the cost of dinner and a movie.

Dating also obscures its purpose by combining courtship with entertainment. Going out to a show or a restaurant was something married couples did. Leisure time was to be spent amongst family and friends. Courtship was not undertaken for fun or idle amusement but to find a spouse. A man who courted respectable ladies without serious intent was a rake and a scoundrel. Worse was said of frivolous women.

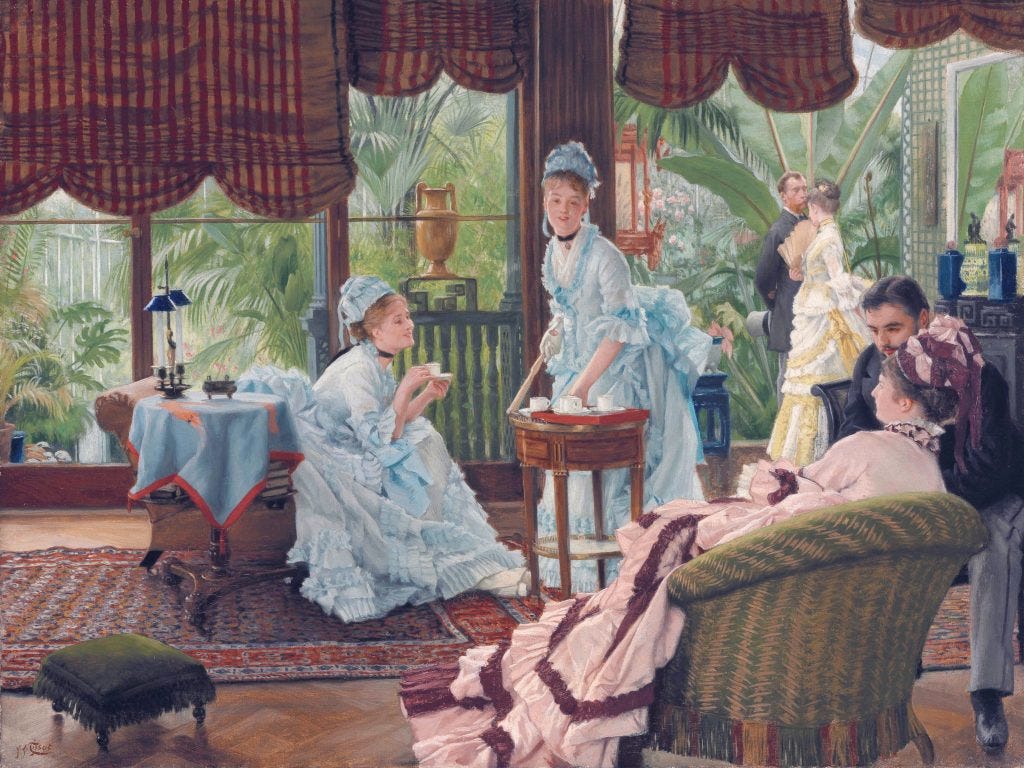

The practice of calling enabled young women to receive guests at home—that is, their parents’ homes. An eligible young woman might meet respectable bachelors at a dance or party and then invite them to visit her during her calling hours. Men would bring their calling cards and show them to the house’s maid. The woman had the right to turn them away if she wasn’t interested or was entertaining another suitor. Because these calls took place within the safety and privacy of the home, a couple could get to know each other while still maintaining propriety.

In other words, calling occurred in a controlled, feminized domain. Early visits required supervision, usually from the girl’s mother. But later visits might allow the pair more freedom, especially if an engagement seemed likely.

The young man might bring flowers or, if the courtship has progressed, gifts to display his affection. The young woman might serve refreshments or play piano. However, the financial and emotional investment involved in calling was limited for both sides. It was more important to dress well, follow etiquette and be a good conversationalist.

The calling system went out of style for various reasons—urbanization and the rise of the automobile ushered in dating as a preferable alternative. However, calling was also quite restrictive and placed considerable influence in the hands of the girl’s parents. Many young people of both sexes wanted more control over spouse selection.

Before the Enlightenment, courtship had actually been less formalized, with less parental oversight. This is because society had a far more rigid class structure before the late 18th century. A well-defined social hierarchy placed natural limitations on courtship. As these class boundaries became more permeable, respectable families sought to maintain authority over the courtship process and protect their offspring from reputational damage in an increasingly confusing world. Thus, calling was born.

The strict control over courtship and sexuality during the height of the calling system was likely unsustainable. I don’t think we can return to any of those past models, but fortunately, how we find love and choose partners is always changing. If we can learn something from those gentleman callers and their ladies, perhaps it is the value of clear expectations and guidelines.1

For more information on this topic, the excellent history book From Front Porch to Back Seat by Beth L. Bailey is highly recommended. The works of popular social historians like Kate Lister and Lucy Worsley also inform this post.

Great essay! It's funny — older styles of courtship can seem a bit boring, but it's as if the dullness is part of the reason they work.

Since today's dating is so entertaining, it's not always clear if a relationship is just held together by the entertainment itself. But in the situation you described, if a man got bored with visiting a country house to give gifts and make polite conversation, or if a woman got bored with serving refreshments and hearing his personal pitch, they wouldn't have much reason to continue the courtship.

Of course that kind of courtship is hardly realistic anymore, and it had its own limitations, but it was a good example of a social script where the goal was clear and particular by everyone involved.

While we look upon such times as quaint vestiges of our past, I suspect in reality that these social mores made more sense than the current world of romance through the internet and dating apps. I'm thrilled to have met my wife before all of this nonsense took off - dating in the 80s, 90s, and 00s wasn't *that* bad; personally, I had a lot of fun. And I got the impression that most women did, too.

It remains to be seen how the coming generations will navigate the dating landscape that has been thrust upon them, but one wonders if they will reject it all and if a resurgence of men approaching women in person will take off. I'll certainly be encouraging my boy to approach women with kindness and openness; it's already so clear that the apps are the antithesis of good "dating".

Great writing as always, Theresa!